Do Cellos Have Truss Rods?

We have come a long way in instrument design since the illuminations in manuscripts that we find from the Middle Ages depicting some of the earliest forerunners of the instruments still used today. Most of us do not pay much attention to the technical features of our instruments until we reach more advanced levels of musicianship. Eventually in our musical journeys, we achieve a familiarity with their design and a technical vocabulary that allows us to speak about them meaningfully. The further we get along in our playing, the more this technical familiarity becomes necessary. As musicians, we often say that an authentic artist does not blame their instrument for their playing—that they can make beautiful music with any working instrument. “There are no truly bad instruments, only musicians who need to practice more.” But, as any guitarist will tell you, sometimes you need to adjust a truss rod now and then. Or do you?

Let us return to that shortly. We all know that there is such a thing as a broken instrument. Instruments can also be intact, but virtually unplayable even by the best cellists because of a poor set-up. All one needs to do is explore YouTube videos where professional musicians review poorly made instruments to see that even they can struggle. An adage with which we are all familiar is that one ought to work smart, not hard. A musician is often required to do both in order to improve, and working smart can include knowing when your instrument is holding you back because a poor set-up, and wisdom is knowing how to fix it. Those YouTube musicians are skilled enough and know enough about their instruments such that they can blame the instrument’s quality, and no one would deny them it. This is possible for all of us.

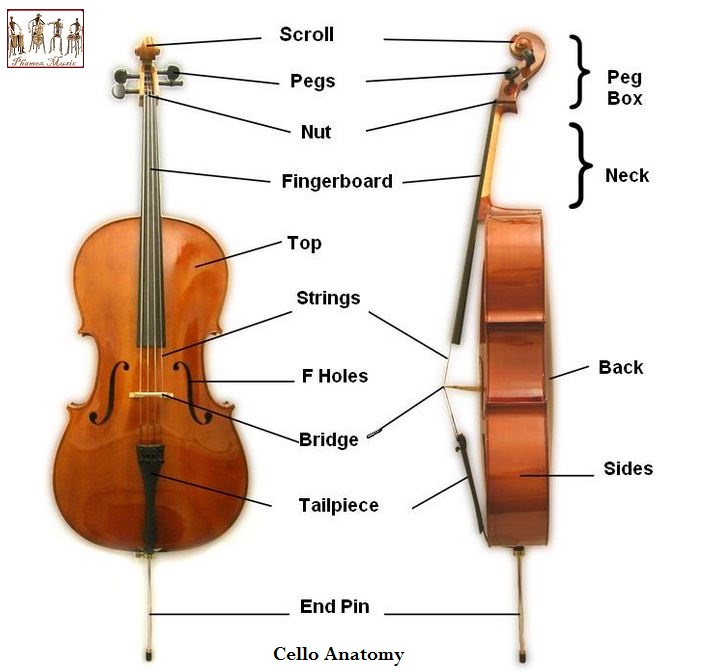

So, what is involved in the set-up of a cello? What work might I need to have done on mine as part of routine maintenance and repair? How can I adjust the action (i.e., the height between the fingerboard and the strings)? As cellists, we find ourselves in a different situation than, say, modern guitarists who play instruments designed more or less within the last century. Modern instruments have many clever design features that are not found in older style instruments, and many of these features make them far easier to adjust and set-up—that is, far easier to play with a good set-up instead of struggling with a problematic instrument. Before I was a cellist, I was a double bassist, and even the double bass has features that I wish would be adapted to cello. Who among us has not been jealous that double bassists struggle only with tuning keys/geared machines on the pegbox instead of the wooden tuning pegs and fine tuners that we cellists have to wrestle with? Nevertheless, as cellists, we understand the aesthetic and historical significance of wooden pegs. Indeed, the violoncello has not changed much in the last 400 years other than tweaks here and there to facilite new kinds of string and bow technologies and new styles of playing that were developed over that time. Ancient instruments are made and maintained with ancient technologies and technical skills that were intended to be performed by artistans and craftsmen. They do not come with specification sheets.

You might say that the violoncello, unlike the modern electric guitar and bass guitar, is something of an heirloom instrument, and this is true for many instruments in the Western European classical oeuvre: resistant to change for the sake of preserving a certain sound, a certain style, a certain timeless aesthetic, both visually and aurally. As a result of its elegant and ancient design, one thing remains: cellos are difficult to set up for those who are not professional technicians and luthiers familiar with cellos specifically, and it is generally not recommended that you set up your cello on your own without these qualifications or significant experience with the instrument. If tuning can be often be challenging enough for beginners and professionals alike, you can imagine how difficult it would be for a novice attempting to carve out the bridge to adjust the action, plane the fingerboard, set the soundpost, or even just replace the strings, especially when a cello’s bridge is not attached and the tail piece floats from string tension alone. Modern guitars, on the other hand, are often relatively easy to work on by design, even for non-technicians. While I have re-strung my bass guitar many times, and while I have even adjusted the fret intonation on its bridge, the only thing I trust myself to do on my cello and double bass is to replace a single, broken string. Even that I would rather pay a professional to do just to spare myself the frustration it can cause!

Despite the obstacles we have as cellists, it is important to understand how your instrument is set up and how it works. Though you may never attempt these things yourself, you will still find yourself in a position to ask others to work on your cello. A good technician/luthier will be able to diagnose the issues with your cello set up on their own, but we all have our own preferences, and it is important to be able to communicate the need for certain repairs or maintenance. Guitarists, to their credit, often have a good handle on this. It is not uncommon to find a guitarist who might say, “Well, the factory recommendation for my instrument is a string height of 2.6 mm on the low E string, but I want the technician set mine to 2.4 mm because I like the lower action, and because I want them to use a thicker gauge string, and I know that increases tension on the guitar’s neck.” As cellists, we are not likely to make much ado about these small things, but you might be encouraged to explore your instrument and find the Goldilocks Set-Up: the set-up where everything is just right.

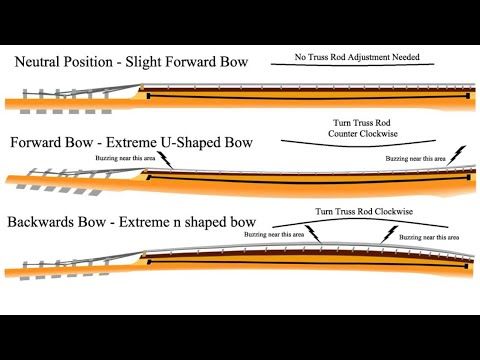

For a guitarist, a set-up like this will involve things like adjusting the height of the bridge anchors, filing the nut, adjusting pick-up height, and tightening or loosening the truss rod to straighten the neck against string tension. Truss rods are a feature of modern guitars: adjustable metal tension rods placed inside their longer, more slender necks that can provide a curvature against string tension and wood warping. This curvature assists in changing the string action, the intonation (pitch accuracy) of the frets, and it can also fix “fret buzz”. Fret buzz is a bane for guitarists, a noise caused when strings vibrate against frets when the string height is too low and the neck has been warped. A cellist does not have to worry about frets, and, as an acoustic instrument, cellos usually are not played with pick-ups of any kind, but it is still important to carve out the nut, bridge, and fingerboard to make the action playable and the tone resonant. This delicate work requires woodworking tools instead of hex wrenches, and that is why it is typically not done by the musician.

But what about the truss rod? Will you ever need to adjust the truss rod on your cello? Though guitars must keep an eye on the ever-changing curvature of their instruments’ necks and adjust accordingly (and often with great anxiety), that is something that cellists do not have to worry about. The design of the cello pre-dates the use of truss rods, and, as such, the necks of cellos are built to resist bowing. You might have noticed how thick the necks of violins, violas, cellos, and double basses are compared to those of guitars and even bass guitars. Cello necks are often about as thick as they are wide, and they are made out of hard maple wood. The design of the floating tail piece anchored to the end stopper (which surrounds the opening for the end pin) helps to distribute tension throughout the body of the instrument as well. It is possible to adjust the curvature of the fingerboard itself, but this must be done by planing and sanding it down directly to the appropriate geometry. The neck, itself, is not made to be adjusted in any way.

This is good news and bad news for cellists. One can simultaneously appreciate the straightforward elegance and simplicity of this design. It prevents the problem of neck bowing entirely without the need for periodically fixing it. If you're interested in learning to play the cello, check out cello lessons in Beaverton. The downside is that it also prevents most of us from working on our own instruments and finding our own Goldilocks Set-Up without a lot of fuss and the help of an extremely patient luthier. Sadly, it also means that adjustments to cellos can be very expensive. My guitarist friends are often shocked when I tell them that routine string replacement and adjustments on my instrument can cost $800 if I want it just right, and most cellists form relationships with specific luthiers and technicians who are attentive to our set-up needs.

So fear not: there is no truss rod to adjust in your cello. There is only everything else!