Why is Music History Important?

I am a music historian—also known as a musicologist in more recent generations. I have been asked this question in many different situations: Why does anyone need to know about [classical] music history? My parents have asked me this question, which can feel painfully invalidating toward my life choices. My students in music history courses often mutter this question, which can be wearily demoralizing. Contrary to what we sometimes think when we are students ourselves, a teacher does not exist to punish us with knowledge, but to enlighten us with it, and that is always easier on teachers when their audience is receptive.

It may seem silly that a classical music student—and even some professional classical musicians!—would not care all that much about studying music. However, this is not all that unusual. How many chemists focus on studying the history of chemistry? How many pilots write books on the history of aviation? The history of a field is something that is often thought to be reserved for the bookish sort, the kind of person who prefers to read and write about it instead of doing it. Indeed, that is often the criticism of a musicologist by other musicians, typified by the old adage: Those who cannot do, teach. I would counter that by saying, Those who will not learn, they often will not do well.

Let us look at a standard list of reasons why you should study music history as both a listener and a musician (and as both a player and a composer). These are the reasons I heard when I was a student, and they are likely reasons you have heard already:

- You have to, so just do it.

- It is important, though I will not really tell you why. Just trust me.

- Everyone else in your field will know about it. Do you want to seem like you do not know what you are doing?

- It will make you a better musician.

These answers were never all that satisfying to me, and I actually wanted to be a music historian! It seems to me that musicologists would do better to explain what we do and why rather than try to convince anyone of the value of musicology. If it is valuable, then it should be self-evident. If not self-evident, then at least we can dig deeper and try to uncover why, exactly, so many musicians do think that a music history education is an integral part of musicianship.

So, what does musicology do? If I were a saleswoman trying to sell it to you, I would say, “Well, what doesn’t musicology do?” Perhaps this is why musicians often shy away from it, the characteristic vagueness employed when defending it. However, there is some truth to this flamboyant claim. Music historians engage with the full picture of musical culture when we characterize music and its social, cultural, and historical function and meaning. We do not simply pour over textbooks and memorize the dates when Beethoven premiered each of his symphonies so that we can torture students with an exam where they have to regurgitate it, only for it to be quickly forgotten. If you want to learn more about music, check out music lessons in Beaverton.

We read manuscripts to learn how to read ancient styles of notation so that lost works can be performed, and so that forgotten composers can have their oeuvre celebrated once more. We work with luthiers to recreate instruments from the past. We work with performers to give them insights in how to interpret a piece of music in a field of study called performance practice. We catalogue the musical works of composers so that they can be republished and disseminated with greater ease, sometimes working out who wrote what when there is a question about such things. More succinctly, what we do is find the answers to questions about music—questions often asked by musicians and audiences themselves. We are not just historians memorizing musical facts for our own sake, but the archaeologists who unearth those facts. For those who study ancient music, that is often not an analogy!

Consider the following situation. You are 14 years old, and you buy an album of Anner Bylsma playing J.S. Bach’s suites for solo violoncello. (Well, you probably downloaded it or streamed it nowadays.) You have played the Suite No. 1 in G Major for years now. For you, it is practically an exercise or an etude, something all cellists play as relative beginners, and it almost seems silly that this great professional has a whole album dedicated to performing them—no, two albums! Nevertheless, you listen to his playing, and you cannot deny that there is something unique about it, something that separates you from him. How does he sound so good? Any cellist can play these pieces, but you ask yourself why you have never sounded that way. This is no longer an etude: it is an artful work of music. For years you struggle with this, wondering if there is something about his cello that is better than your own, or maybe you are just so poor of a musician that, while technically correct in your playing, you sound mechanical and disjointed compared to him. What does he know that you do not?

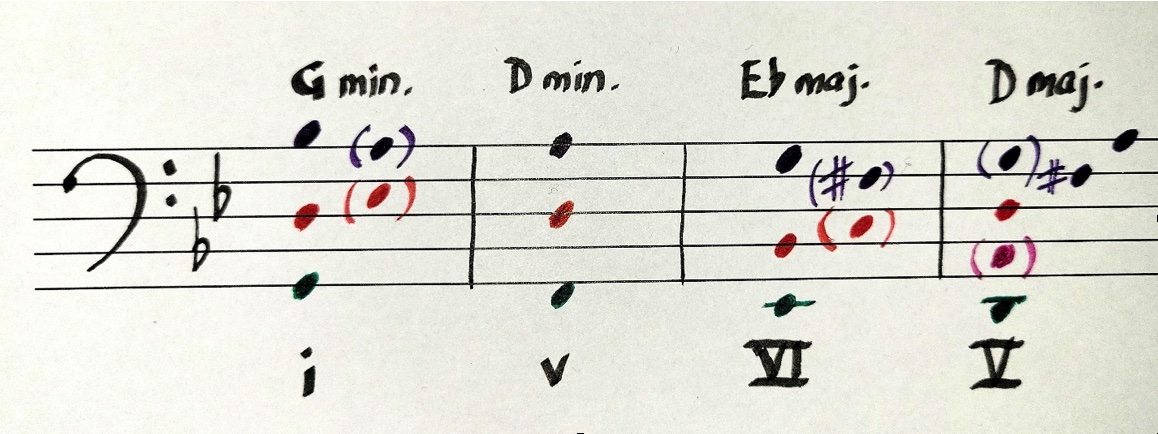

Fast forward, and now you are 18 years old. You learn what Baroque music is, and you learn about basso continuo and monody: two terms describing musical textures common to the period in which Bach wrote his cello suites. You also learn about tonal harmony, a compositional technique involving the way pitch is organized in this style of music, a way to create a sense of tension and rest, an aural drama of anticipation. You learn about phrasing and cadence, binary form (how the music is organized thematically through larger timescales into two sections), and voice-leading (i.e., how musical parts in an ensemble distinguish themselves while combining into a harmonic whole), and lastly, something related called polyphonic melody. The reason why you could never sound as musical as Bylsma was not because you were not playing the right notes, but because you were not playing the notes right. That is, you were not playing the cello suites as if there were multiple parts hidden among the notes, a technique that is well-understood when you get the full picture of Baroque style, something you only learn studying it in its historical context.

It comes together in your mind instantaneously when you discover what Baroque music really is and how it works, knowing where the cello suites fit historically in terms of compositional style, Bach’s artistic goals, and historical performance practice. You listen to Bylsma’s playing once more that evening, and every seemingly arbitrary bowing choice, every position shift on the fingerboard, even the trills and ornamentations he adds: everything makes perfect sense. At last, you tune up your cello, and, even though you have been practicing that piece for many years, it sounds like interesting, complex, sensitive, artful music for the first time. Though it had eluded you for years, all it took was listening to a music historian talk for 50 minutes. You just had to know that there were three parts in one, and, not only can you now play it, but you can also hear it and understand.

Example: Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1, Minuet 2, played by Anner Bylsma

Example: Score for Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1, Minuet 2, polyphonic melody highlighted in three voices

Example: Ibid., first four measures normalized to show harmonic progression and voice-leading, known as the “Lament Progression” in Baroque musical rhetoric

Not everyone will have these moments of discovery all the time, but studying music history oven leads you down other paths. As another example, I never had any interest in classical sacred vocal music (i.e., music for singing in church). When I was introduced to Fuxian counterpoint and the music of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, I was transfixed. Now I transcribe music notation from the Middle Ages that cannot be read by most modern musicians, and I have performed such works with a church choir that may not have been heard in six hundred years. These pieces brought tremendous joy to a great many people in audience, and that itself was a fantastic reward of digging deep into neglected realms of musicological exploration. You just never know what you might find.

You may only know about a fraction of the music you enjoy, or at least would enjoy if you did, indeed, know about it. You may be unable to understand and appreciate the music you already know. You may have a problem in your playing or listening that is waiting for an answer. Music has never existed in a vacuum because it is a truly human activity, and it is bound by human culture and experience. Successful musicians understand the history of those cultures and experiences, and music’s place within them, and they have broadened their musical pallettes (and, often, their own artistic tastes and inspirations) on the basis of that understanding and the curiosity it breeds.

So I invite you to answer some questions about music that you have, and to ask questions that may not have been asked before. Everyone benefits from it, and not just as a parlor trick, recognizing the Brahms trio on the radio and knowing the year he was born so that you can impress someone. Ask any enthusiastic hip hop fan for an explanation of a favorite artist, and they are likely to give you an in-depth historical account of them, their life and works and the context of the tracks they show you, as well as the place of that artist in a cultural milieu. Such things are no less important for classical musicians, composers, and audiences alike—and no less fun to discover! Music history is not just for music historians, nor even just for musicians. It is part of our shared world history and heritage, and it belongs to all of us.